A beam is a horizontal structural member that spans some open space and is supported near the ends. The beam can then support some weight placed on top of it somewhere between the end supports. A floor joist is a beam. Concrete countertops are also beams.

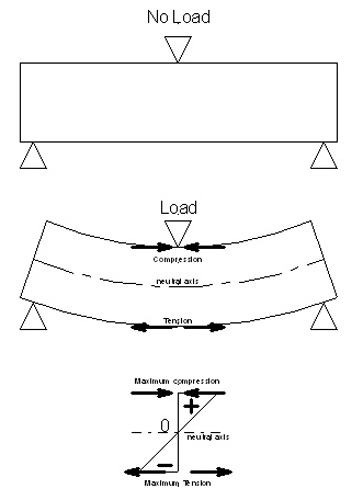

When a beam has weight placed on top of it, that weight causes the beam to deflect (bend). Small weights on stiff beams cause almost no deflection, while large weights on flexible beams cause significant deflection. The deflection in the beam causes two things to happen: The top surface of the beam is compressed and tries to get shorter, and the bottom surface is in tension and tries to get longer.

Between the two something important occurs. Compression is the opposite of tension, so as one progresses down the beam from the top surface to the bottom, the compression stress gradually decreases to zero and then the stresses reverse, go into tension and gradually increase towards the bottom of the beam. If an unreinforced beam has a symmetrical cross-section (like a rectangle), the stress switch occurs at the midpoint between the upper and lower faces.

This is important because given that there is no tension or compression stress at the midpoint of a countertop, placing reinforcing steel there does absolutely no good. The point at which this switch occurs is called the neutral axis, and can be thought of as an imaginary line that runs parallel to the length of the beam.

If a countertop is made out of traditional precast concrete (with no reinforcement), any significant weight placed on top of it will cause it to fail at the bottom of the countertop because the tension stresses in the bottom of the countertop will exceed the tensile strength of the concrete. A crack will form at the bottom and progress upward literally at the speed of sound.

Note that in the case of GFRC concrete countertops, the structural reinforcement is provided not by steel but by AR glass fibers mixed in. Literally, it is “Glass Fiber Reinforced Concrete”. Please see the extensive free GFRC articles on this site to understand how GFRC works.

Some argue that because concrete countertops usually actually span only the width of a cabinet box (usually a maximum of 36″), they are rather short beams, and therefore the stresses involved are not that high. This is true, but what about when an 8 foot long precast slab is picked up in the shop and loaded onto a truck for transportation? The largest stresses and biggest risk of cracking occur in the shop. Once the slabs are installed, only settling of the cabinets or building would impart much stress.

This video goes much more in depth on the subject of compression and tension forces in concrete countertops.